The Saddle

Its Construction, Function & Malfunction

CONTENTS:

Why a Saddle?

The Saddle - To Stay On

The Stirrups

Classy Leg

The Saddle - For Comfort

Bridging & Rocking

Lumpy Bumpy Pressure Points

Padding, and Other Ways of Separating Yourself from Your Horse

Three Fingers in the Channel

Saddle Placement

2 Inches Behind the Shoulder

Influence Through the Saddle

Choosing a Saddle

Why a Saddle?

Indeed, why use a saddle on the horse, when we want to keep it natural? To stay on? For comfort? To spare the horse's back? Yes to all of the above.

The reasons to use a saddle are many, even for those using their horses for the same purposes. There are even more reasons, when you consider the different employments horses have in our world.

An absolute beginner at the riding school becomes very much aware of the reasons he needs a saddle to begin with. And the way riding is taught at most places nowadays, a saddle is needed from the word go. You come to the school, get a saddled and bridled horse, get helped up, and get to trot standing in the stirrups, while you try to cling on. And in the modern affordable riding school environment the teacher has 10-15 students to tend to, so you are left to your own devices for most of the time.

At the Spanish Riding School, things are different. Students there have the privilege to be taught the mysteries of the balanced seat by two specialists; An extremely accomplished human guide, and a bareback well schooled stallion. At th end of a lungeline, without the crutches of cantle and stirrups, balance is sought for more than a year, if needed. There is no way these men will ever learn to push against the cantle from the stirrups, sit in a chair seat, or lean in and fall on the outside seatbone. If they try, they fall off. They will learn to accomodate to the horse's moving center of gravity at all times.

The Saddle - To Stay On

Huge thigh blocks cram you into position. By the higher pommel and cantle, the rider sits a lot more secure in the saddle than on the bare back. The higher the pommel and cantle, the sturdier the seat. This extends beyond what is good and useful, and can actually block the correct seat and aids of the rider by "securing" him in a position. These extreme saddles have become very popular lately, and some even have enormous thigh blocks added, without any embarrassement, on the outside of the saddle, not at least trying to hide it under the flap.

This is said to give the rider a firm and plumb seat, and certainly it does. It is just that there is no room to move the legs back and forth to give different aids. There is also no room for different stirrup lengths, which would be useful for riders whose hips are not yet supple enough to be seated without almost any bend in the knee. These bumps push the thigh much further back than most riders, even accomplished ones, are physically agile for. This results in a rotation of the pelvis instead, so that the rider is seated more or less on the crotch.

The plumb position that we are striving for cannot be found with blocks, any more than collection can be found with drawreins. The desired position comes from relaxation and balance, nothing else. See further under The Balanced Seat under The Training Scales of Horse and Rider.

Huge thigh blocks cram you into position.

The stirrups

not only help the rider climb onboard. They help the rider keep his balance in the saddle, and helps him relieve the horse's back through posting to the trot, stepping on the stirrups. The weight of the rider is suspended and shock absorbed by the knees as the rider rises and sinks. The actual weight on the back is the same, but the roughness of a stiffly thumping rider can be mercifully avoided. Besides tradition and safelty, there's really no reason for competitors in the ring to have stirrups. The weight of the rider is suspended and shock absorbed by the bend in the knees as the rider rises and sinks. The actual weight in the saddle is constant, but the roughness of a stiff thumping rider is smoothed out. In young, remedial or correction horses, the gaits might even be so rough that even an experienced rider has no chance of sitting smoothly. In finer riding, an aid called "stepping into the stirrup" is used, and for that, one needs a stirrup. But competitive riders hardly use it.

At the shows of the Spanish Riding School, the leaps and airs above the ground are performed without stirrups when mounted. The reason for this is unknown to me, but I guess tradition has something to do with it.

Drawing heels up, standing on the toes.

For everyday riders, still learning (and aren't we all) the stirrups can be a source of many vices. First we have the tensing of the foot to pressure the ball of the foot down against the stirrup. This is, of course, totally counter-productive, but oh, so common. Before one has learnt to drop the leg down the horse and let the foot fall into the stirrup, one desperately tries to make the stirrup stay on the foot by dipping the toes. If all beginner riders had to ride without stirrups, until their legs hung down correctly, many gripping knees and stiff ancles could be avoided.

Pushing heels down pressing against the cantle.

The pushing down of the heel is next, and occurs when the rider has painstakingly learnt to give in the ankles. The legs still need to drop down, and so we push by trying to straighten the leg. This pushes the lower leg forward, and the unbalanced chair seat, with rump to the cantle and heels on the horse's shoulder is made.

This is not only hideous to watch and a nuisance to the rider which flops around on top of the moving horse. It is a real problem to the horse and his back. This, because when the rider pushes back from the stirrups, he pushes himself back towards the cantle and moves the entire weight back to the rear of the saddle. This makes the weight of the rider land on the 1/3rd at the rear end of the saddle. This concentrates the weight on a smaller area of the back, and an anrea which is less stable, too. Now add to this that the rider is inbalanced and thumps, and you have a hollowing horse on a good day, and an injured back on a bad say.

Next, the rider is saved too many times, when centrifugal forces has thrown him to the outside. He can learn and reinforce in both himself and his horse, that 75% weight in the outside stirrup and folding to the inside, plus hanging on for dear life to the inside rein, is normal. Without the stirrups, the result would have been a sore buttock for the rider and surprise for the ridded horse. Drifting to the outside is one of those things that can only be cured by riding without the stirrups.

Keeping the stirrups on the feet, or keeping the feet in the stirrups is also one of those things that one has to learn. And once you have learned it, it never goes away.

As usual, focus is on the symptom, not the cause, and I have seen it "cured" with insulator tape, extremely short stirrups, etc. All in order to get the dang stirrup stuck to the foot!

The problem does not lie in the stirrup nor in the foot. Not in the lower leg at all. It's in the hip.

Riders still fighting this problem, don't usually have problems keeping the foot in the stirrup, nor to look fairly correct with a lowered heel and everything, when the horse is at standstill. It's keeping it that way whilst under movement that is hard, and especially in trot. Why?

Because the rider can relax and drape his legs around the horse when the horse is not moving. Thus the foot can land in the stirrup and the weight of the lower leg can rest against it. But as soon as the horse starts to move, the rider cannot relax the leg. Either the rider grips in a futile attempt to stay on or make the horse thump less because that is uncomfortable, or simply because they "do" so much when they ride.

Or, the leg was not correctly draped to begin with. The hip adductors have not relaxed, and are pulling the upper thighs together, leaving the rider sitting on the muscles of the back of the thighs or with the legs rolling over the pumped muscle on the inside of the thigh. This muscle must be flaccid in order for the leg to be draped.

A tense hip makes the upper leg bounce and move with the gait. This happens just like in the shoulder, where tense shoulders make the arms flap and makes for an unsteady bouncing hand. How does this happen?

When you try to relax the tense hip, most muscles do relax. So much so that they flab. One muscle alone can still be tense pulling the thigh in the direction forward/up. In the phase of the step when the whole horse is moving forward/up these muscles help getting the thighs forward and up too. But when the horse turns, and starts to fall down, these muscles don't stop their lifting of the limbs. The "weightlessness" that happens as the horse turns and starts falling down makes the thighs/arms lighter. So the muscle pulling upwards/forwards suddenly has no resistance and the thight is jerked even more forward/upwards. This adds to the movement so much that the rest of the leg, and thusly the foot, alights from the stirrup. And does not necessarily land on it when coming down.

When the hip is relaxed, the weight of the leg, from the mid-thigh down, rests in the stirrup. Horse, rider and stirrup move up and down, with no extra flapping and the foot rests in the stirrup, maybe not with the same amount of pressure through the phases of the step, but always some pressure downwards.

Unless the stiffness in the hip is solved, there is no pushing down of the heel in the world that can help. And shortening the stirrup leathers will only cure the symptoms of not allowing the leg any room to bounce. It blocks the leg from its optimal position, where the rider can feel and influence the horse the best!

Classy Leg

Stirrups under the tip of the toe.

Most riders wear the stirrup on or slightly behind the ball of the foot. This I presume, because they sometimes rise to the trot, and thus want to "tread" steadily on the stirrup. But this is not the optimal position for the seated gaits. When seated, the weight of the leg, or a part of it, should rest in the stirrup, and that is not very much. You can actually just rest your tippy toe on the stirrups, and still have an nicely draped leg, a lowered heel and look gorgeous. Or rather, just because you do, you can.

If you look at the big boys from the classical institutions, they all wear their stirrups on the utmost tip of the boot.

The Saddle - For Comfort

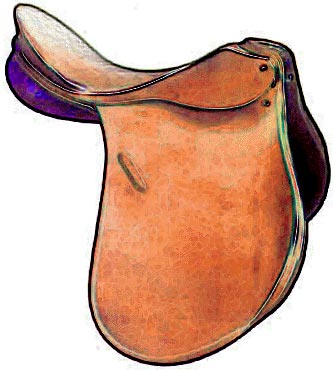

To make it easier on you and me both, I will describe the traditional english saddle type, which is the one used in competition within the FEI, and to be honest, by most dressage riders in general. There are other saddles, som of them specialist saddles for difficult-to-fit horses, to avoid backpain in riders or even those who find normal saddles to be sub-optimal and are trying to find a better way. Some names are the Ansür, Reactor Panel, Torsion, etc... I hava not tried any of them, and will thus say nothing about them.

The saddle is a relatively straightforward construction wich less variation than one would think. The traditional saddles are built around a tree, which acts like a skeleton. This tree pretty much decides the shape of the saddle,

and of the greatest importance is the angle between the two points in the front. They decide the width of the saddle, and that is paramount for fit, and it usually cannot be changed easily. The exception to that is the Wintec system with interchangable gullet irons. This one I have used, but I can't say I like the rest of the artificial leather saddle. There are probably other interchangeable gullet systems as well.

The angle of the points is set on most older saddle trees, as well as the location of the stirrup bar. In more modern saddles, both the width of the points and the stirrup bar can be exchanged or moved. On some saddles one can even do it oneself.

It is usually riveted onto the steel part of the tree. This is important to look for when buying a saddle, because since it cannot be moved, nothing can be done if it doesn't fit you. In older type saddle it is common to have the stirrup bar placed too far forward.

The girth billets are also mounted on the tree. If the billets break or need to be changed, the saddle must be taken apart, to reveal this part, and change it.

Costly. The tree is covered in fabric and struufed to some degree with wool for rider comfort, and then completely covered in leather, both on top and underneath. Under this tree are the panels, which are really two long rolls of leather filled with stuffing. They are attached in front and at the back paralell to oneanother so that the space inbetween creates the channel for the horse's spine. They also continue down the sides of the horse in the direction where the points are pointing. In the photo you can see the small pockets where the points of the tree go. Then there are flaps and sweat flaps attached and the saddle is complete.

The seat of the saddle has the inverted shape of a human rump. The weight of the rider's body can be effectively spread over all of the surface of the seatbones, and the buttocks and thighs, and make the weightbearing area larger than just the seat bones. This is a lot more comfortable than sitting on a straight log. Or even a bare back for that matter. The spinous processes of the horse's back, are fairly narrow. When riding bareback the rider sits with the better parts, whether man or woman, directly on these 1-2 inch wide bony structures. A well muscled back helps to upholster some, but compatibility is not 100%.

The saddle from underneath.

But we are not only talking rider comfort, here. Horse comfort is just as important. Or should I say, even more important. Since the rider chooses to rub his butt vigorously for an hour or more every day, he can suit himself if it hurts. But the horse has no say unless the discomfort turns to injury or worse. Since a horse has much less motivation, and a much shorter attention span than his rider, discomfort is totally counter-productive to correct work. One way of creating discomfort is by pointing two fairly narrow seatbones into the latissimus dorsi muscle of the horse, and weighing it down with the weight of a human. A saddle will more or less efficiently spread the rider's weight across a much larger area of the back of the horse. And which would you prefer, had you to choose between a rock and a hard place; to be stepped on the foot with a sneaker or a high heel?

The underside of the saddle is of utmost importance to the horse. It rests against his back weighed down with the rider's weight. But not only that, The horse moves the shoulders and its muscles with the leg movements, bends the rib cage left or right and lifts or hollows the back enclosed by the saddle. The saddle is still a fairly ridgid piece of equippment, irregardles of new inventions, spring trees etc. The horse must move and alter his shape inside this ridgid confinement.

It is important that the saddle lies flat against the back so sthat the pressure is even. The horse's back will change in shape as soon as the horse starts to move. Optimally, the back arches some to compensate for the weighing down of the riders weight. Also the back bends left and right at the walk and trot, and the latissimus and other muscles moving the shoulders, move in under the front end of the saddle. In a well fitting saddle, there is leeway for that. In a saddle with pressure points, there is not.

Bridging & Rocking

Two major faults in saddle fit are bridging and rocking. This means the the entire shape of the saddle is mismatched to the horse's back. A bridging saddle is too straight under, laying like a log on the back, bridging from withers to mid-back. The saddle does not rest on the thoracial back where the rider sits. This causes increased pressure at the withers and at the mid back. It also causes the saddle to move about because of the lesser contact surface to the back. In any case, it causes pain, soreness, abrasions and sometimes open wounds around the withers and the back of the saddle. It can ruin a prefectly good horse.

The longitudal misfit of saddles - bridging and rocking.

Rocking is a subtler problem. It is the opposite of bridging, meaning the saddle is too round under, like the hull of a boat on flat land. This causes the saddle to rock back and forth with the gaits. This causes the same pain, soreness, abrasions and wounds as bridging, but naturally, right under the riders seat.

Saddles like these simply don't fit. Economy usually makes riders want to restuff or pad up or whatever, to make the saddle fit, but that's just like bad shoes. Get new shoes. It must fit from the start and it's too much to adjust through stuffing.

A lot of riders sit in crooked saddles. I don't know why this is so, but saddles crooken with time and use. Well made saddles less, and cheaper saddles more. Saddle fitters often talk about broken saddle trees and other bad flaws in a saddle, but that requires a flip-over fall or some kind of accident. Dressage riders who never come unseated think their saddles free of such problems. And to a great extent they are. But saddle trees can also wear off slowly, or slowly become crooked or twisted, no accident needed. You need to check this often, especially if you have an inexpensive or older saddle.

Lumpy Bumpy Pressure Points

This is the biggest problem of older saddles. The stuffing has rearranged itself into nice little lumps and filled out the softer spots of the leather of the panels. The heat and sweat of the horse will cause the leather to stretch, and when the least uneven, it will stretch unevenly. In the places where it will stretch more, there will be a bulge. This bulge will fill up with the stuffing, creating a bump, or a lump that will cause more pressure over a small area. Exactly the same thing will happen to that area, as will happen when a saddle bridges. The area will rub and bruise, even cause open wounds. Most of the times, it will just cause a bruise that cannot be seen - only felt - by the horse and yourself. The horse will seem unwilling to release the back, or bend, or become "girthy" or try to bite.

There is a product called "the Impression Pad" commercially available on the internet, that seems much easier than my procedure below. For saddle fitters or businesses this might be something to look into: The Impression Pad

Otherwise, you can make a rub print.

Take a few of those old carbon copy papers, and if you dont have one, take any coloured paper that will rub off slightly against a white surface. Sometimes a slight spray of water from a vaporizer will help, and put this paper face down on white paper and put that under the saddle (preferably all of the panel surfaces) and adjust the saddle like you normally would. Use your regular numnat, and if you must, you pads. Ride for an hour or whatever you usually ride. Take off the whole arrangement, and look at your white paper. Depending on how dirty your horse is, you might need to trace the outline of the saddle onto your white paper to be able to see what rubs where. If you find smaller areas of more rub, you need to investigate your saddle. If you get rub at the pommel and cantle, your saddle might be bridging. If you get more rub on one side, your saddle, your horse or your own body might be crooked. Go fix!

Padding......and Other Ways of Separating Yourself from Your Horse

Oh, all these space-age-tech pads! They do more harm than good!

Most riders I know pad up under the saddle out of care for their horses. They don't want the saddle to rub, and they want to soften their own thumps, and soften the horses thumps so they can sit, and so on. In the long run this does not work.

A saddle of resonable quality will be soft on a horse's back. If it's hard, you should really investigate in some re-stuffing or a new saddle.

A saddle pad of even thickness raises the saddle more infront.

If a saddle fitter has fitted your saddle, he has most likely done so without the extra pads, because that's how a saddle is supposed to sit. To add extra pads would be like a human shoe-fitter were to fit you shoes, and then you would add 2 pairs of extra socks to make them "softer". The shoes would be too small. It is the same thing with saddlefit, only that it is the area at the head of the tree, the gullet width that is crucial. If you put a 1 inch thick pad under the whole of the saddle, the front would lift more than the back, because the area for the withers would be too narrow for the saddle.

A saddle pad makes the saddle tighter infront, and it tilts back.

The thickness lifts the saddle more because the pad is at an angle to the body of the horse. Lifting more infront would mean that the saddle tilts back. This is usually the opposite to what one would want, since most riders seem to be sitting too far backwards anyway, pressing the back of the saddle down. With a thick pad underneath, this is even more exaggerated.

As the saddle is pressed down behind the panels flatten and narrow the channel. In older and cheap saddles, you would usually try to counteract the fact that they have been sat down at the back. The back of the panels have been pressed together and to some extent they have become flat and spread to the sides and into the channel. In saddles like that, you can't simply re-stuff, because the shape of the expanded leather is set. It has the boated out form and it's permanent. In a saddle like that, you need to change the entire panels (if you like the seat that much) or buy a new one. And it's not even probable that you would like the seat if the panels had been changed - at least not if it's you who have sat it down at the back, anyway. That means you WANT to sit at the back of the saddle and press it down. New pandels would lift the back and skid you forward. You might not like that at all. Get a new saddle.

Some pads are made of gel encased in a plastic bag of sorts. This is made to cause trouble. The airtight plastic will cause the horse to sweat, which can cause extra strain on the skin and hide. The gel can cause the saddle to rub back and forth because its gluey and lets the saddle move sideways and back and forth. It can cause the rider to move about more than he otherwise would, and most of all - it makes the distance from the rump to the back increase, and disables the rider from feeling the back of the horse, and the state of relaxation from its movements.

This is especially evident in the new lines of air-inflated saddles. These are said to be extra nice to your horse's back. Some firms even use a doormat of air inflated footprints for one to step on with ones bare feet, to feel how nice it feels. And to bare feet, it sure feels nice. But in everyday use, a parallel would be if you were to put these footprints into shoes and walk around in them. Is that easy, you think? If the saddle evens out all the pressure created by the rider, how is it then possible to give distinct seat aids. they will be muddled, of course.

The air-inflated saddles I have ridden in have all been over-inflated. The airbag has acted like a big rubber ball, that makes you bounce. They are also inevitably voluminous, and separate you from the horse.

The real reason for the numnah, is for the horse not to put sweat on the saddle so that the water and salt will ruin it. It is supposed to wick the moisture off the horse and stop it from coming in touch with the leather. It would be perfectly possible to use the saddle without any pad at all. In fact, for horses who get rubbed bare from the saddle pad, the solution would be to use the saddle without the pad. The woven fabric of the pad catches the hair as it rubs back and forth with the movements. Plain leather is very slippery so it doesn't rub as easily.

A sheep-skin half numnah.

If the horse gets awfully sweaty the sweat can ruin your saddle. In that case, a sheepskin numnah is ideal, but try to find one that is relatively thin, and only has sheep skin under the panels! The sheep skin adds volume between the saddle and the horse's back. The curly hairs stay with the hairs on the horse and the skin part can move with the saddle, and it is ventilated enough to let the sweat evaporate. But you don't need that on the sides. Adding an inch or half-inch of thickness between your leg and the horse unnecessarily complicates your communication and feel.

Three Fingers in the Channel

3 fingers should fit into the channel.

The last, but fairly common subject of saddle fit that I hear when out and about is the width of the channel between the panels. The channel is made to give clearence to the spinous processes on top of the back. This is absolutely necessary. No weight must rest upon the processes - that would lead to pain that could become chronic. The saddle is meant to rest entirely on the ribs sprung out of the thoricial spine. So the saddle weighs the spine, it's not that. The skin and ligaments on top of the processes may not be squeezed. So the channel gives clearence to the spine.

But in order for this to happen, the channel must be wide enough to accomodate the processes, and it must follow the line of the spine. A wide enough channel will still put pressure on the spinous processes if the channel is crooked, or the horse constantly bent to one side. Remember, the saddle only bends very little with the horse, if at all.

The measure that has been around for decades is 3 fingers. You should be able to fit 3 fingers beside each other into the channel, and move it freely all the way from the pommel area to the cantle. The problem area of the compressed saddle is usually the back of the panels. Look extra carefully there.

Lately, saddle fitters have begun a new deal. 3 fingers are no enough. Now we need 4. And I wonder...

I don't know if this is the same case as with the snaffle design of olden days - that modern research has verified that a lot less room is available in the mouth and that snaffles ought to be thin and double joined with a bean in the middle. Simply that techology advances. Or if it is that saddle makers want to sell new saddles, just like car dealer want to get rid of all those nice old cars from the good old days because they last forever, and sellers don't get to sell. (I ought to know - I own a classic volvo that just keeps on going.) Sellers go on about safety, or rather saddlers go on about horse care.

I don't know whether to think there's something to it, that many horses struggle with back pain and it goes unnoticed. Or whether I think they just want me to give up my 30 year old Passier and buy a new air inflated hi-tech saddle for more than the cost of the horse!

There is also another possibility. It could be that 3 fingers are just too narrow. Being 3 fingers of a petite girl saddling and riding a big warmblood horse. Girlie desktop fingers. 3 heavy duty military man fingers are something else. Maybe they equal 4 lady fingers. Time will tell, I guess.

Saddle Placement

Don't place the saddle too far forward, on top of the shoulderblade.

So many riders are terrified of placing the saddle too far back. Some prevalent myth of the sensitivity of the kidneys or equal usually scares them to obedience. And this is truly bad for the horse.

To begin with, I'd like to explain that the kidneys of the horse are about 4 inches below the surface of the back. If the saddle is pressing there, you need another saddle. Now, the loins are sensitive, sure. The area around the whirl is quite soft on a horse since the horse has no true ribs there. So you need to look out if you have a horse with a short back. The thing is, that the horse will start to have problems with the back under the rear end of the saddle, if you put the saddle too far forward. Any well fitting saddle will lean backwards if placed on top of the shoulder blades, too far forward on the withers.

Gusseted panels add insult to injury.

The tilt will cause the saddle to bridge between the shoulders and the area under the back of the panels. This will increase the pressure at these points, and added to this, the rider will weigh the saddle further back since it slopes back and the rider slides back against the cantle. Gusseted panels tend to add insult to injury.

2 Inches Behind the Shoulder

The placement of the saddle tree on the horse's back.

The saddle has two points at the front of its tree, to help the saddle retain it's shape to keep the withers free from the pressure of the saddle. This pressure instead lands on the sides of the withers, behind the shoulderblades. These, and the rest of the underside of the saddle are well upholstered into the panels of the saddle and should not become pressurepoints as such, but the fact remains, that the saddle is built on an immobile skeleton with this shape.

The saddle is placed too far forward blocking the shoulder blades.

If the saddle is placed with these points on top of the shoulderblades or too near behind them, they will rub against the shoulderblades with every movement of the frontlegs. The forward and backward movement of the shoulderblades happens because the muscles under the saddle pull them back to advance the limb, and the shoulderblades and muscles will slide in under the saddle points and increase the pressure under the saddle. This area will become sore and the horse will be reluctant to move scopey with his shoulders. This hindrance will have repercussions throughout the back and the horse can end up with pain and injury anywhere. Or become girthy and buck riders off.

Influence Through the Saddle

The seatbones mark the saddle seat.

Many riders and trainers speak of the seatbones and the horse's back. Some more conceptually of "plugging the seatbones into the back" but some actually more physically. Some speak of "pushing the seatbones into the back of the poor horse" and such things, which I must say is plain silliness. The saddle is a thick construction with a skeleton made out of wood or plastic fibre, and there's no way that a human's seatbone, can be felt through the saddle.

If you, in good Zen tradition, want to test this yourself, bring a friend. Put the saddle over the lap of your sitting (sturdy) friend, and have a seat. Scoot, skimp, wiggle and hump all you want. It may be uncomfortable for your friend (going ex-friend?) but he/she won't be able to feel the seatbones. No, siree!

What CAN be felt, however, is the different weight on the different seat bones, which translates to the right or left pandel on the saddle. This is very important in steering and bending, so it is vital to dressage training.

Something else that can be felt is the way the rider uses his seatbones, that is his pelvic tilt. When you "engage the seatbones" several things can happen depending on how you have learned to do it. Mostly riders push the pelvis forward, so that it is placed in front of the plumb line from the ear.

The pelvis remains vertical but pushes against the front pommel.

This can have a driving effect on the horse, if the abdominals are well engaged. The tensed abs make the torso "go with" the forward phase of each step, and thus make the rider go with the movement in the exact phase when it is needed, and the horse is encouraged to extend or transition up. The same poise in the saddle can also have the absolute reverse effect, if it only means that the upper body leans back. This moves weight back, which, at its best, has a collecting effect, but generally only slows or hollows the horse.

If the pelvis is rotated around its horisontal axis, in the way that the seatbones are pushed forward and the upper rim of the pelvis is rolled back, which is what a lot of riders do to engage the seat bones, a lot of things happen. First of all, the pelvis itself cannot rotate, since it is stuck like glued onto the vertebral column and the fused vertebraes called the sacrum. There is no moving joint around there. So the small of the back actually has to flatten its natural curve in order to rotate the pelvis. So the small of the back, this suspension spring, is straightened.

Many riders stiffen the back by tucking their pelvis.

So the seat is stiffer, and the rider thumps. The seatbones move in under the rider, and the pubic bone lifts from the saddle so that the rider sits on the back edge of the seat bones. This is equivalent to rocking on a chair balancing on the back legs - very little stability. This gives an unstable seat.

Many riders have this kind of seat. They stabilize it by leaning back towards the cantle and then bellydance with each step, as they rock back and forth on the back edge of the seat bones. The horse slowly gets used to this and learns to ignore it. The horse also ignores the increased shoves that the rider makes to drive the horse forward. This shoving rider and sluggish horse thing can escalate on and on.

Choosing a Saddle

In choosing a saddle it is paramount that it fits the horse. No horse will work in a good way with an ill-fitting saddle. Even if the horse does his best during mild discomfort, he will also learn to be insensitive and ignore the seat aids.

Next, it is important that the saddle fits the rider. Riding in a saddle that is less than comfortable is voluntary on your part, but not very good in the long run. A misplaced or tense rider is not the best partner even for a horse in total comfort himself.

Saddles are the same as shoes. Only of late have women realized that they might need a size bigger that they'd wish. Men, especially riding men, tend to have small buttocks and fit into quite smaller saddles than a lot of women who have bigger bums than their male counterparts, but also a strong whish to be petite. Don't do yourself this unfavour. Accept your hind end!

If you ride in a saddle which is too small, your buttocks will push your crotch forward against the pommel. This can be less than comfortable, to say the least. You will fight this by pushing back from the irons, and push against the cantle, which will push the back of the panels down into the back of the horse. Your discomfort is suddenly his.

But this is not the only size that matters. The most common undetected problem riders have with saddle fit is the width of the twist. Most saddles are made for Venus of Willendorf - wiiide hips! Most riders have narrow hips, or stiff hips, or are petite in general, or ride biiiig horses which automatically come with a wide saddle.

The thickness of the panels can hamper communication.

Most newer saddles have such an incredible amount of stuffing both on top and in the panels that they are like straddling a jumbo jet. Avoid it! A saddle does not need to be wide in the twist because your horse is wide (or overweight) and just because your rump is big does not mean the space between your thighs are. The older type of saddles, like Passiers or Stübbens, some Lemetex, Kloster Schönthal and Courbette are thinner and narrower, which will serve you well. And buying second-hand will serve your wallet, although take some time.

The thickness of the flocking of the panels also influence your time in the saddle. It is very popular to not only have a very thick saddle, but to also add to the tickness with extra pads and numnahs that are not really needed. Look at the two saddles to the right. The thicker Jaguar saddle is of the modern, overstuffed type. The seat is small and the cantle is high. Not much space to come down into the saddle close to the horse's back. The thinner saddle is of the wellknown older type, a Passier, which is one of the few companies who continue this tradition. Their seats are usually roomier too, and the twist is narrow. An excellent way to get close to your horse.

A word of caution on too big saddles. This is not very good either. Don't automatically buy the 18" just because there is one. You will not like to ride in such a thing in the log run. If your seat is usually unstable, you will skid and scoot around inside the seat of this saddle, and because of it start to grip and do bad things. Avoid that too. A rider with a very good, balanced seat, will have no problem with a too big saddle, since such a rider is not dependent on the saddle to stay in one spot. But please be honest with yourself about your riding skills, too.

|